Urban streetscapes in a major city may appear to be an unlikely environment to find leaner and greener practices. However, the Chicago Department of Transportation has shown that it is not only possible to make sustainable upgrades to city streets, but that such upgrades improve the quality of the landscape and the livability of the community in many ways.

Background

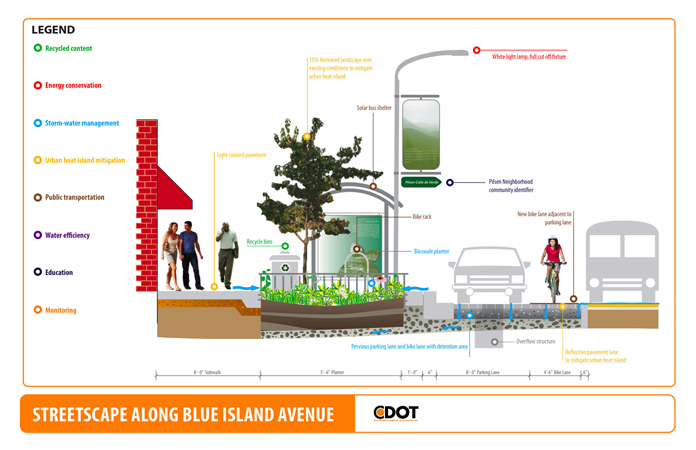

To demonstrate the scope of sustainable practices in an urban context, Chicago DOT used a grant from the Federal Highway Administration under the Eco-Logical program to help transform an approximately 2-mile stretch of urban street on Chicago’s south side. Known as the Cermak/Blue Island Sustainable Streetscape, the project follows South Blue Island Avenue and West Cermak Road along the South Branch Chicago River. In addition to the FHWA grant, the $14 million project was funded through Tax Increment Financing, as well as grants from the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency and Midwest Generation.

Planners and designers identified several performance goals for the project. These include:

- stormwater management,

- water efficiency,

- multi-modal transportation improvements,

- energy efficiency,

- use of recycled materials,

- reducing the urban heat island effect,

- air quality improvements, and

- education, beautification, and community development.

Phase I has been completed and Phase II, a portion of South Blue Island Avenue between South Wolcott Avenue and South Western Avenue, is underway, according to Janet Attarian, Project Director for the CDOT Streetscape and Sustainable Design Program.

Stormwater management feature, Photo Courtesy of Chicago DOT

CDOT held a dedication ceremony on Oct. 9, 2012, to highlight the successes of Phase I of the project. In announcing the completion of the first phase, CDOT Commissioner Gabe Klein said the project “demonstrates a full range of sustainable design techniques that improve the urban ecosystem, promote economic development, increase the safety and usability of streets for all users, and build healthy communities.”

CDOT said the first phase of the project has achieved a number of sustainability goals:

Material Recycling and Innovation: the first commercial roadway application of photocatalytic cement, which cleans the surface of the roadway and removes nitrogen oxide gases from the surrounding air through a catalytic reaction driven by UV light; the recycling of more than 60 percent of all construction waste and the sourcing of more than 23 percent of all new materials from recycled content; the first installation of sidewalk concrete with 30 percent recycled content in the city; and the first installation of roadway asphalt that includes reclaimed asphalt pavement, slag, ground tire rubber, reclaimed asphalt shingles, and warm mix technology.

Stormwater Management: the project diverts up to 80 percent of the typical average annual rainfall from the combined sewer through a combination of bioswales, rain gardens, permeable pavements, and stormwater features; the creation of two public plazas that infiltrate stormwater and include seating and educational opportunities.

Water Efficiency: the elimination of the use of potable water for all landscape irrigation; the piloting of 95 drought tolerant, native plant species in bioswales, and infiltration planters to evaluate effectiveness in roadside conditions.

Energy Reduction: the project reduced the energy use of the street by 42 percent and used dark-sky friendly light fixtures; installed the first permanent wind/solar powered pedestrian lights and the first LED pedestrian light poles on a streetscape in Chicago; 76 percent of all materials used were manufactured and extracted within 500 miles of the project site; and 23 percent of all materials were within 200 miles of the project site; piloted use of microthin concrete overlay to extend pavement life and increase solar reflectance.

Urban Heat Island Effect Reduction/Air Quality: the project included high-albedo pavement surfaces to decrease the urban heat island effect, representing 40 percent of the total public right of way; provided a 131 percent increase in landscape and tree canopy cover; used ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel for construction vehicles.

Community and Education: the project developed community identity with education kiosks, a walking tour brochure, and a guide book in Spanish and English that provide a wide range of information about the sustainable best practices used in the project.

Alternative Transportation:the installation of a pedestrian refuge island in Cermak Road adjacent to Juarez Community Academy, and curb-corner extensions throughout the project, in order to improve pedestrian safety; one half mile of new bike lanes on Blue Island Avenue; improved bus stop areas with signage, shelters and lighting.

Monitoring and Evaluation:modeled and monitored stormwater best management practices to analyze design, ensure predicted performance, and determine maintenance practices; performed air quality testing to analyze photocatalytic impacts on air quality; and developed a maintenance protocol with the community to transition maintenance responsibility from the city over a two year period. For the first time, the project required that a streetscape contractor fully track and document the use of recycled content, recycled materials, and local manufacture and extraction on the project.

Site Chosen for Mix of Uses

The site was chosen because it includes a complex mix of uses that made it especially attractive for testing different design elements, according to project manager David Leopold, with Knight Engineers & Architects. The neighborhood includes a park, a high school, commercial real estate, a power plant, a brick yard, a scrap yard, a nonprofit organization, and, only a block away, residential areas.

One of the main goals of the project was to balance the needs of the all the existing users while at the same time minimizing the ecological impact of the uses, all in a limited amount of space, according to Leopold. CDOT made an effort to find opportunities for ecology “based on the limitations of our urban area,” Leopold said.

Another goal was to push the technology for sustainable infrastructure, Attarian said. As a pilot project, the design goals set a very high standard and a lot needed to be done “to make sure that [technology] would be available for us,” Attarian said. For example, for the photocatalytic cement CDOT had to find a domestic source willing and able to produce it, according to Attarian.

Another example is the high albedo pavement used in the project. The concrete mixes were developed and tested by CDOT, using slag and lighter aggregates

Key to the effort was realizing that “a single design mode can have multiple benefits,” Leopold said. As an example, bioswales are effective at trapping stormwater to reduce the amount of runoff flowing into the city sewers. They also serve as a buffer between the pedestrian space and the street. In addition, they provide habitat for birds and insects. Finally, they are attractive, serving to beautify the area and promoting economic development in the process.

In addition, the project was intended to be a laboratory to learn how to design, build, and install sustainable infrastructure. CDOT wanted to find out “what we [could] do if we try to take advantage of everything we had” in terms of innovative technologies, processes, and practices, according to Attarian.

The redesign of one streetscape provides a blueprint that can be scaled up to address stormwater issues, the urban heat island effect, and other sustainability issues throughout the entire city, both Attarian and Leopold noted. What was developed for and learned from this project will be standardized and implemented as much as possible citywide. CDOT has received information from the project’s contractor on what worked and what did not work, information that will be instructive to new efforts going forward, Attarian said.

“A big part of what we are doing is education,” Attarian said. There is education of CDOT employees on how to use the new materials and design principles. The project team is developing a set of sustainable urban infrastructure policies that will be publicly available.

In addition, public education is integral to the project. The FHWA Eco-Logical grant aided in the purchase of the hybrid wind- and solar-powered information kiosks placed along the sidewalks to provide educational material about the streetscape design.

Lessons Learned

There were several lessons learned from the design and construction of the project, according to Attarian. They include the following:

- integrated design requires new roles within interdisciplinary design teams;

- technology availability may not always coincide with project schedules;

- changing “business and usual” within a public right of way requires communication with all users;

- monitoring local pilot projects is critical for the accurate comparison of grey versus green alternatives; and

- addressing livability issues within the public right of way involves inherently sustainable practices.

CDOT has installed the means to perform ongoing monitoring of the sustainable materials and techniques, including the monitoring of stormwater, pavement and air temperatures, and air quality. This monitoring was not required, but rather it was “what we wanted to do” to learn from the project, Attarian said.

More information is available on the CDOT Streetscapes and Sustainable Design website, http://www.cityofchicago.org/city/en/depts/cdot/supp_info/streetscapes_andsustainabledesign.html. Additional information is available by contacting Janet Attarian at (312) 744-3100), [email protected], or David Leopold at (312) 742-4772), [email protected].