An online tool developed by transportation and environmental agencies is helping transportation officials in Maryland identify watershed restoration and mitigation opportunities for projects.

The Watershed Resources Registry was developed by the Environmental Protection Agency, the Federal Highway Administration, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Maryland State Highway Administration, and others. Launched in the spring of 2012, the web-based tool is being used to identify opportunities for watershed restoration or mitigation in connection with federally funded projects requiring compliance with federal environmental and transportation laws.

According to a fact sheet, the geographic information system (GIS)-based tool was developed to analyze watersheds and identify the best opportunities for the protection of high quality resources, restoration of impaired resources, resource conservation and planning, and improvement of stormwater management.

Maryland SHA is using the tool to assist in avoidance and minimization of impacts during planning, design and maintenance operations, according to Sandy Hertz, Deputy Director of SHA’s Office of Environmental Design. Additionally, the tool is used to prioritize watershed needs when a construction project requires mitigation. SHA staff gathers environmental inventory information and identifies potential mitigation sites using the registry.

The Watershed Resources Registry helps MDSHA locate high-quality wetland mitigation sites, such as Lizard Hill, in Maryland. Photo: MDSHA

The tool also helps with initial field reconnaissance by providing data that can be exported to a print map, including GPS coordinates for navigation. The tool helps to streamline information collection and preparation for permit processes, aids in National Environmental Policy Act and state environmental reviews, and is used to justify mitigation site selection as part of the review process. In addition, the tool allows SHA to achieve multiple goals using limited resources.

Recently, SHA used the registry in the preparation of the MD 4 Project Planning Study Preferred Alternative Concurrence Package, according to Hertz. Based on acreage replacement ratios agreed upon by the Corps of Engineers and the Maryland Department of the Environment, the proposed project would require just under one acre of compensatory mitigation for wetlands. A review using the tool was completed to identify potential wetland mitigation sites in the Patuxent River and Lower Potomac River watersheds. The registry identified significant acreage with potential for wetland restoration within both watersheds, Hertz said.

Web-based Model

The tool, which can be publicly accessed over the web using typical web browser software, includes an abundance of data for identifying restoration or preservation opportunities, including maps, GIS layers, GPS coordinates, federal hydrological unit codes, and an analysis of the ecological needs of each parcel.

Source: Watershed Resources Registry

Users typically would begin with the “find opportunities” template. The template guides in the selection of opportunities for restoration or preservation in compliance with one or more federal resource statutes and includes four ecosystem types:

- uplands,

- wetlands,

- riparian (rivers and streams) areas, or

- stormwater-impacted areas.

The WRR Technical Advisory Committee has created a ranking system applicable to each opportunity by performing suitability analyses. Each watershed or waterway segment has a score of 1 to 5 based on these analyses and is mapped using GIS data.

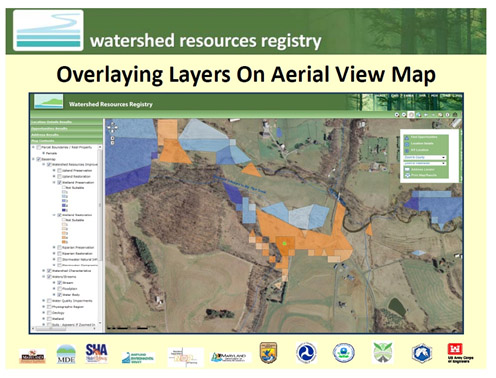

Once opportunities have been identified, various GIS layers can be switched on or off, including satellite imagery, and the locations can be viewed at multiple scales, showing their spatial relationships to nearby features.

When a site is selected, the tool provides location details that include the reasons the parcel is suitable for a mitigation or restoration opportunity and its particular ranking. For instance, a site with a score of four for stormwater compromised infrastructure restoration means that a significant number of criteria that reflect the disruption of the natural hydrologic system by stormwater are present at that location. The criteria were developed through the suitability analysis process.

A user can access the tool to identify sites that are consistent with environmental regulatory requirements and have the best potential for mitigation or restoration based on available data, according to Dominique Lueckenhoff, Deputy Director of EPA Region III Water Protection Division.

The tool includes a training video for new users, technical documentation about the suitability analyses, and a user guide. In addition, there is access to all the underlying data that allows for more sophisticated GIS analysis, according to Ellen Bryson of the Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District.

The tool currently contains data only for the state of Maryland, but its internal architecture is flexible enough to eventually serve other states and jurisdictions, according to officials who have worked on the registry from the beginning.

Developing the Registry

The registry began as an idea for using a watershed-based approach for planning a transportation project in Maryland, Lueckenhoff said in an interview. In 2006, discussion had begun on plans for improvements to U.S. Highway 301 in Charles and Prince George’s counties, in Maryland, that would use the “green highways” principles, taking a watershed approach to sustainable infrastructure planning and delivery. As the various agencies came together on the project, there was talk about a “watershed bank” that would “become a multiple end-user product” and achieve benefits beyond just the one project to address U.S. 301, according to Lueckenhoff. “It could serve future projects and help preserve and restore resources, in addition to being supported through various credit markets,” Lueckenhoff said.

It was clear that the U.S. 301 project was trying something new. The Maryland SHA along with federal and local agencies were attempting to build a highway in such a way that both the transportation needs and the environmental needs were met within a highly sensitive area encompassing four watersheds, according to SHA’s Hertz.

Starting with a geographic information system (GIS) and data on watershed resources developed during the U.S. 301 planning, the WRR partners also added the regulatory requirements of the various statutes that affect watershed health, said Denise Rigney, an environmental scientist with EPA Region 3. The desire to bring the needs of watersheds earlier in the NEPA process and other planning processes led to the registry concept, Lueckenhoff said.

There was a “groundswell of partnership in Maryland,” said Lueckenhoff, allowing for the product to eventually expand statewide. There was support from the top for this, Lueckenhoff said, but more importantly, it was built from the bottom up, addressing the needs of those at the field level.

The usefulness of the Watershed Resources Registry has exceeded expectations, Lueckenhoff said. All of the team partners – EPA, the Corps of Engineers, Maryland SHA, and FHWA – are using the tool.

Other agencies are using the tool as well. Field inspectors are using it to preview sites before a visit, local agencies are using it, and there is growing interest from the public. “There are uses that we didn’t even imagine it for,” Lueckenhoff said.

Interagency Collaboration

One of the most satisfying things is that the registry is the result of successful interagency collaboration, officials said.

It “evolved out of the willingness” of the various agencies to step outside their comfort zones, Lueckenhoff said.

This cooperative environment has been exciting, Bryson, of the Corps of Engineers, agreed. By bringing together the various types of information into one integrated tool, people are creating new kinds of information that weren’t possible before, said Bryson. Members of various agencies can coordinate over the web and be assured that they’re all looking at the same thing. “All the agencies are together on this,” Bryson said.

The agencies continue the development process by meeting once a month to discuss improvements. As data change, they will be added to the tool, Bryson said. As new models are developed, the tool will be tweaked to accommodate them.

Also going forward, sites that are identified by the tool will be inventoried with site visits, and information regarding selected or completed restoration projects will be added, said Ralph Spagnolo, a wetland hydrologist with EPA Region III and a member of the WRR Technical Advisory Committee.

The Baltimore District of the Corps of Engineers includes portions of Pennsylvania, and Bryson said that a roll-out of the registry using Pennsylvania data is likely.

In producing a registry for another state, developers would be able to take advantage of the eight pre-existing suitability models in the Maryland WRR and start with available federal and state data, according to Lueckenhoff. An interagency technical advisory team or committee should be established (or utilized if one already exists) to collaboratively identify stakeholder needs and interests and evaluate to what degree the data and existing models are able to address them.

Due to the work done already, the next state will be able to develop and use its registry in significantly less time than it took for the initial development in Maryland, according to Lueckenhoff. The team already has been approached by several Mid-Atlantic States for transfer of the WRR to address a variety of needs, Lueckenhoff said. “It is highly adaptable, without being overly complex and challenging to multiple end users. This is a pretty good [model],” she said.

The registry has been selected to receive technical assistance from AASHTO’s Technology Implementation Group, chosen as a National Water Program Best Practice by the EPA, and included in a handbook issued by the Environmental Law Institute.

The Watershed Resources Registry is available at https://watershedresourcesregistry.org/. For more information, contact Dominique Lueckenhoff ([email protected]) or Ralph Spagnolo ([email protected]) at EPA, or Sandy Hertz at Maryland SHA ([email protected]).